On April 15, 2024, Angola didn’t just tighten rules-it shut the door completely. The government issued a nationwide ban on cryptocurrency mining, making it illegal to operate any mining equipment, possess mining hardware, or even connect to unauthorized power sources for digital asset extraction. By August 2025, authorities had dismantled 25 illegal mining centers, seized $37.2 million worth of equipment, and arrested 60 Chinese nationals running the operations. This wasn’t a random crackdown. It was the result of a country running out of electricity-and choosing its people over profit.

Why Angola Couldn’t Afford Crypto Mining

Angola’s power grid has been on life support for years. With a population of nearly 40 million, the country only has 5,500 megawatts of total generating capacity. That’s less than 140 watts per person. For comparison, the average American uses over 1,200 watts per person. In cities like Luanda and Benguela, 60% of households face daily blackouts. Hospitals rely on generators. Schools lose power during exams. And yet, crypto mining farms were pulling 15% of the entire national grid’s output during peak hours. The math was brutal. Mining operations, mostly run by foreign operators using ASIC miners and GPU rigs, were consuming between 50 and 200 megawatts continuously. That’s enough electricity to power 300,000 homes. One Bitcoin mined in Angola used 1,440 kilowatt-hours-40 times more energy than a single bank transfer. The government didn’t hate Bitcoin. It hated the fact that its citizens couldn’t turn on a light while miners ran 24/7.How the Ban Was Enforced

The ban wasn’t just a law on paper. It came with teeth. Operating a mining rig without permission carries a prison sentence of one to five years, plus automatic confiscation of all equipment. The National Electricity Agency (INE) started scanning smart meter data for abnormal 24/7 power usage. Any facility pulling more than 10 kilowatts continuously got flagged. Industrial-scale operations over 100 kilowatts became top targets. In August 2025, Interpol’s Operation Serengeti 2.0 turned up the heat. Angolan police, trained in thermal imaging and power signature analysis, raided sites based on tips from locals. A whistleblower program offered 5% of seized equipment value-up to $50,000-for information. That led to 73% of raids coming from community reports. One resident in Sambizanga told investigators: “Our clinic couldn’t run an X-ray machine, but the mining farm next door had three industrial transformers.” Seized equipment included 8,300 ASIC miners and 15,000 graphics cards. Many were connected to illegal power stations-unauthorized transformers and bypassed meters that were causing fires and transformer explosions. In one case, a mining farm in Lobito had been stealing power from a water treatment plant. The plant shut down for three days. Over 10,000 people lost clean water.Who Was Mining-and Why They Came

The miners weren’t Angolans. They were almost entirely Chinese nationals, drawn by one thing: cheap electricity. At $0.03 per kilowatt-hour, Angola was one of the cheapest places on Earth to mine. Global average? $0.07. That’s a 57% cost advantage. But the low price came with hidden costs. Miners reported frequent outages-18 to 24 hours per week during dry seasons. Many had to run diesel generators, which pushed their operating costs up by 35%. Others paid monthly bribes of $500 to local utility inspectors just to keep their rigs running. One leaked WeChat group chat showed operators joking about “hiding rigs in warehouses so the grid doesn’t notice.” But the grid noticed. And so did the people. Local businesses suffered too. Electricity tariffs rose 22% in 2023 because the grid was overloaded. Small shops in Benfica, Luanda, couldn’t afford refrigeration. Pharmacies couldn’t store vaccines. The social cost was too high.

Why Renewable Energy Didn’t Save the Day

Angola has some of the best solar potential in Africa-2,200 kWh per square meter annually. Theoretically, it could power entire cities with sunlight. But the government didn’t make exceptions for solar-powered mining. Why? Because the problem wasn’t just energy source-it was energy access. Even if a mining farm used solar panels, it still needed batteries, inverters, and grid connections to stabilize output. And the grid was already broken. The Ministry of Energy made it clear: no mining on the grid, period. Even if you generated your own power, you couldn’t connect to it. The only legal way to mine? Be completely off-grid-with no link to the national system at all. That’s nearly impossible at scale. A single ASIC miner draws 3,200 watts. A small farm of 100 units needs 320 kilowatts. That’s a solar array the size of a football field, plus massive battery storage. No one had the capital or infrastructure to do that legally.What Happened After the Ban

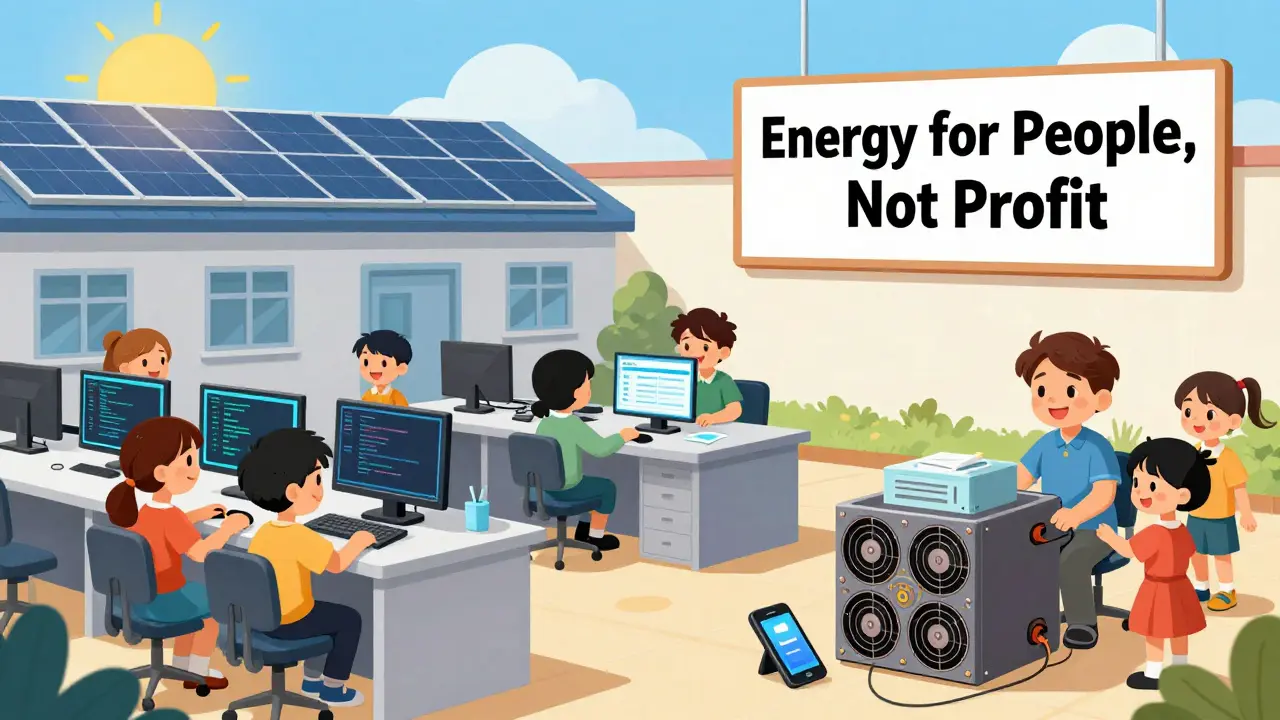

The ban didn’t kill crypto mining in Africa-it just moved it. Namibia saw a 200% surge in mining registrations from Angolan operators. But electricity there costs $0.12 per kWh-four times more than Angola’s old rate. Profit margins dropped by 60%. Many miners gave up. Globally, Angola’s hash rate collapsed from 0.8% to 0.02% of the total network. That’s a loss of 1.2 exahashes per second. The mining industry barely noticed. But Angola did. The government started redistributing seized equipment. 65% went to universities for computer science labs. 35% went to municipal e-government projects. One university in Huambo now runs AI research on machines that once mined Bitcoin. Another city in Malanje uses confiscated GPUs to process tax records faster.

Is There a Future for Crypto Mining in Angola?

The government says no-for now. Energy Minister João Baptista Borges made it clear: “With 15 million people without reliable power, we won’t let digital assets take what our children need.” But there’s a glimmer. In September 2025, President João Lourenço met with Solax Power to explore pilot projects for off-grid solar mining. The condition? Zero connection to the national grid. No borrowing from the public. No risk to hospitals or schools. That’s a narrow door. But it’s open. Experts believe Angola won’t allow any mining on the grid until reliability hits 90%. Right now, it’s at 52%. The Cambambe III hydropower project, set to add 1,150 megawatts by 2028, could change that. But even then, it’ll take $12 billion in infrastructure upgrades by 2030 to get 85% of the population on stable power. Until then, Angola’s message is simple: energy is a human right. Not a commodity for foreign miners.What This Means for the Rest of Africa

Angola isn’t alone. Seven of 15 SADC nations have restricted crypto mining since 2022. But Angola’s ban is the strictest. Nigeria and Kenya let exchanges operate but crack down on energy theft. South Africa taxes mining to fund grid upgrades-earning $120 million a year. Angola’s approach shows something deeper: when a country is on the edge, it doesn’t negotiate. It chooses. And in a place where a child’s life depends on a working refrigerator for medicine, there’s no debate. The lesson? Crypto mining isn’t inherently bad. But when the lights go out for millions, and they stay on for a few hundred miners-it’s not innovation. It’s exploitation.Why did Angola ban cryptocurrency mining?

Angola banned cryptocurrency mining because mining operations were consuming 15% of the national electricity supply during peak hours-enough to power 300,000 homes. With 60% of urban households facing daily blackouts and critical services like hospitals and water plants struggling to stay online, the government prioritized public safety over speculative digital asset mining.

Is it illegal to own a crypto miner in Angola?

Yes. Possessing or operating any cryptocurrency mining equipment without government authorization is illegal under Angolan law. This includes ASIC miners, GPU rigs, and even small setups. Violators face prison sentences of one to five years and mandatory confiscation of all equipment.

Did Angola allow mining with renewable energy?

No. Even solar-powered mining is banned if it connects to the national grid. The government requires any future mining to be 100% off-grid with no link to public infrastructure. No such legal operations exist today, and the government has not approved any pilot projects yet.

How did authorities find illegal mining operations?

The National Electricity Agency used smart meter data to detect abnormal 24/7 power usage. Police used thermal imaging to spot heat signatures above 45°C from mining rigs. A whistleblower program offered cash rewards for tips, leading to 73% of raids being triggered by community reports.

What happened to the seized mining equipment?

Seized equipment was inventoried using blockchain tracking and auctioned if valued over $10,000. Most of it-65%-was redistributed to public institutions: university computer labs and municipal e-government systems. This turned mining hardware into tools for education and public service.

Will Angola ever allow crypto mining again?

Only if the national grid becomes reliable enough to support it without risking public services. Experts estimate this won’t happen before 2027-2028, when major hydropower expansions like Cambambe III come online. Even then, any future mining would require full off-grid renewable power and strict government oversight.

Amit Kumar

Man, I’ve seen this play out in Lagos too - foreign miners showing up like they’re doing God’s work while kids study by candlelight. Angola didn’t just make a policy call, they made a moral one. No one’s saying crypto is evil, but when your grid’s screaming and someone’s running 200kW rigs in a warehouse next to a maternity ward? That’s not innovation. That’s theft with a blockchain logo.